"For the Kids"

By Mitchell Vexler, November 3, 2025

I adopted the 2001 outline from the California Policy Center to prove the Pattern and Practice of defrauding the voters that occurred in California which is the same Pattern and Practice used in Texas with the same result of not only bankrupting the school systems, but equity stripping the property owners and hurting every single citizen.

Texas Voters Must Become Wary of Borrowing Billions More from Wealthy Investors, Banks, Pension Funds and 401Ks for Educational Construction and misapplication of your tax dollars.

Executive Summary:

"For the Kids” – Comprehensive Review of Texas School Bonds (aka Intent to Defraud). Many people suffer from cognitive dissonance or unwillingness to believe what the facts show and wanting to transfer their wishes onto others in society. They would rather claim the school districts would not act in such a manner and they suspend their own critical thinking not recognizing that they too are being defrauded as they too are property taxpayers. The bottom line is that I would not be writing this article “For the Kids” if the School Districts had not intended to commit accounting fraud and bond fraud and then required the Central Appraisal Districts to commit property tax fraud, both of which are violating dozens of laws.

See List of Violations.

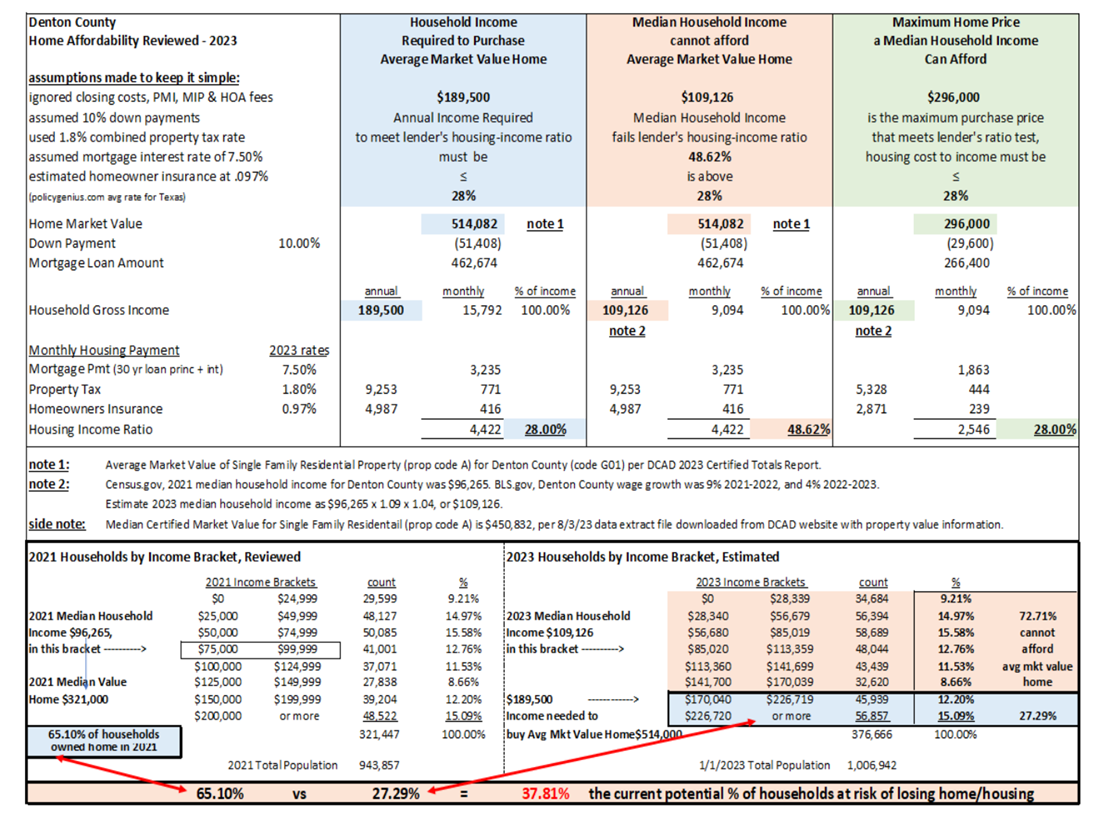

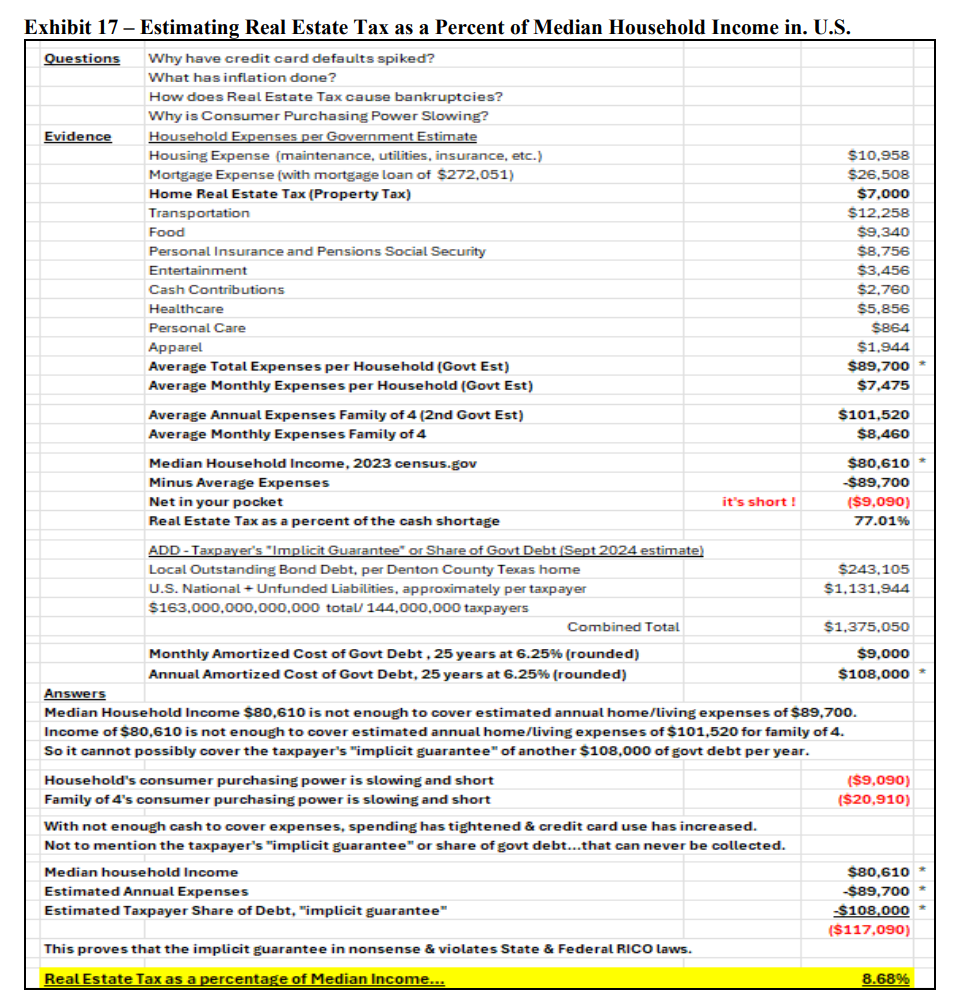

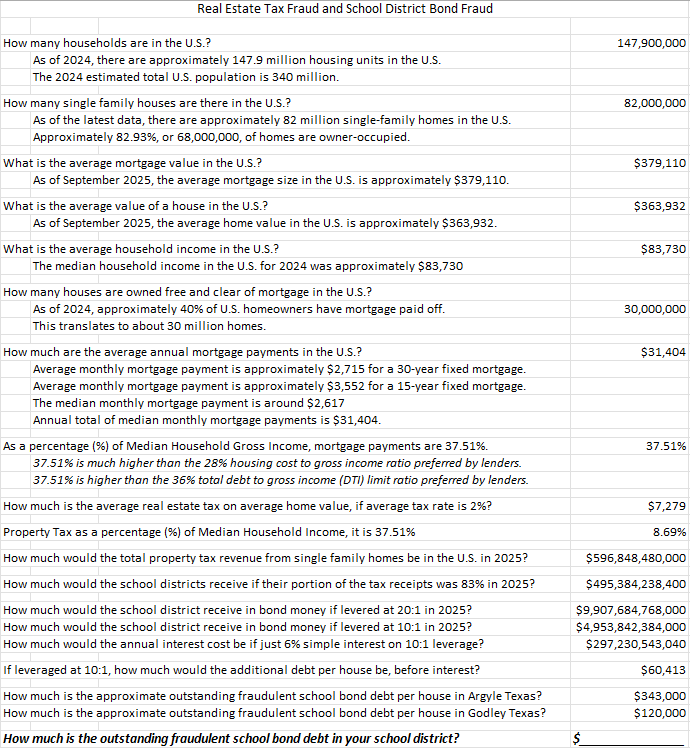

I wrote an article called Hunger, Assault, Repeal the Real Estate Tax. In this article I made the case about over 4,000,000 meals being served by Feeding Texas Network and the way to solve the hunger is the repeal of all property taxes. For those who claim “we are doing this for the kids” are hungry children not important to you?? Is it that you don’t see those hungry faces, so you don’t care? Is it that the story is not on main stream media, so you don’t care? Is it that just like politicians, you won’t admit when you are wrong and will simply allow the children to go hungry, families having to make a choice of food of rent payment, and probably over 37% of the household population going bankrupt because your ignorance and ego is so strong that you would hurt your neighbors, friends, family and even yourself? The reason these questions are so strong is that if those who are promoting the bonds were truly doing something “for the kids” they would be doing exactly what I am doing which is demand the repeal of all property taxes in favor of the Uniform States Sales Tax, as there is no other solution to properly fund the schools, and end hunger in the State of Texas. As a message and personal plea to those who are promoting the bonds; obtain the information, being the total outstanding fraudulent school district bond debt, plus the total outstanding compound interest carry in your school district, divide that number by the households in that district, put the total in an amortization schedule and then stand at a public meeting with press in attendance and show them exactly how the bonds are going to be paid off when the debt averages 70% of the true median value of a home. Prove me wrong by engaging the property owners in your community via your local FB group, at Board meetings, allow other people to talk without a 3-minute limit and realize that the money does not exist to pay off these bonds today and the money will not exist to pay off the bonds tomorrow.

Did you sign a document wherein you gave up your State and Federal Constitutional rights and said document states you agreed to go bankrupt to support your school district? Although this question is rhetorical, it has more meaning in your life than you probably realize.

In this article, I am going to show you that there is a high probability that either you or someone close to you is by definition bankrupt (Liabilities > Equity) and I am going to show you how and who is responsible, and how to gather your own information from your School District.

See exhibit/worksheet below.

What makes the school district bond debt fraudulent?

- Roll the principal payment out and roll the interest rate up.

- Raise additional bonds to pay off the current bonds.

- Utilize a pre-determined budget given to the Central Appraisal District and raise taxes (i.e. property values) to hit the budget outside the confines of the law (USPAP).

- Utilizing an Appraisal Review Board as the exclusive remedy to protest values when the ARB is not capable to determine values and or fraud.

- The CAD raises property values for the purpose of creating revenue to meet the pre-determined school district budget.

- The cost of interest based on the Rule of 72 has outstripped the original principal by multiples.+

- As the property tax is fraudulent then so are the school district bonds. RICO = Creating a false debt and demanding payment.

- There is no such thing as the "full faith guarantee" of a school district - there are no unlevered assets - just liabilities which are transferred to the "unlimited tax" to be paid in the future by the property owners. There is no such thing as "unlimited tax".

- Approximately Twenty Three Trillion dollars in property overvaluation across the U.S. occurred between 2017 and 2025 by the CADs from which roughly $450 Billion was stolen.

Few Texans realize how much debt they’ve imposed on future generations with their votes for bond measures meant to fund the construction of new and modernized school facilities.

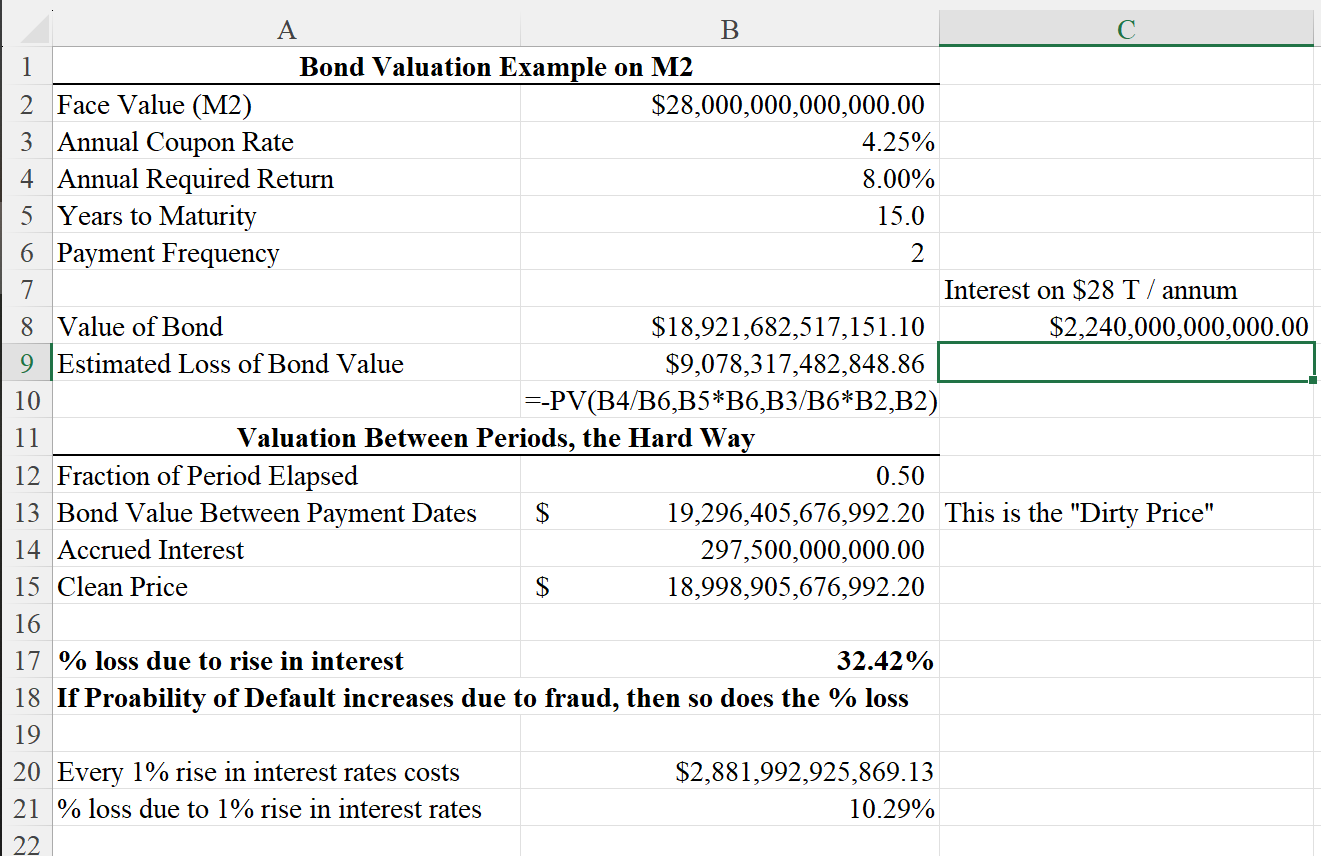

From 2001 to 2025, Texas voters considered ballot measures proposed by K-12 school districts to borrow money for construction via bond sales. Voters approved the majority of these bond measures, giving school and college districts authority to borrow incalculable meaning un-verifiable hundreds of billions of dollars plus compound cumulative interest that is growing by the second. What makes this unverifiable and incalculable? The fact that the data is hidden from you the public. It is estimated by me that the outstanding fraudulent school district bond debt in the State of Texas is approximately $606 Billion.

See the power point pdf article, Credit Analysis and Systemic Moral Hazard = Terminal Failure.

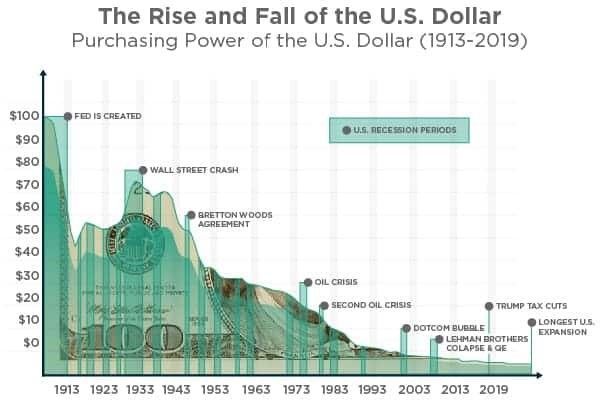

Hundreds of billions have been authorized during the last 25 years for state and local educational districts, which own the Central Appraisal Districts (CADs) to obtain and spend on construction projects and a litany of other pet projects, of which the vast majority of schools have shrinking enrollment, horrific school district test scores, underpaid teachers, bureaucratic fat, gross incompetence and a demonic pledge never to admit the ship is sinking all in favor of bankrupting property owners via Equity Stripping their hard earned equity while they sleep. All of these hundreds of billions have been borrowed or will be borrowed from wealthy investors, who buy state and local government bonds as a “relatively safe” investment that generates tax-exempt income through interest payments. What these wealthy investors are about to find out is that these bonds are anything but “relatively safe”. When these bonds, are added to the compound cumulative interest, not paying off the bonds but rolling them up and interest out, plus the fraudulent overvaluation and over taxation of the properties to support the pre-determined budgets of the school districts, plus the mortgage backed securities, plus inflation both from printing money by the Federal Reserve and the fraudulent over taxation at the CADs, the combination is that or a neutron bomb of financial mass destruction. Neutron because the bomb will leak financial radiation while leaving the majority of physical properties intact, but the bankruptcies will be everywhere.

Current and future generations of Texans are already committed [via the fraud they have been dupped into] to paying these investors billions in principal and interest — a number that will grow as school and college districts continue to borrow by selling bonds already authorized by voters but not yet sold.

And more borrowing is coming.

It is time to be wary. We believe that most Texans are unaware and uninformed about this relentless borrowing and the amount of debt already accumulated to pay for school construction, operations and maintenance (O&M), and interest and sinking fund (I&S). Most voters cannot explain how a bond measure works and do not get enough information to make an educated decision about the wisdom of a bond measure. What they do receive from many School Superintendents and the School District Boards are accounting fraud, bond fraud and intent to defraud.

See the article, Questions to Be Asked of Your School District.

Texas voters who want to learn more before voting will have difficulty finding relevant information. Where does an ordinary Texan find out how much money a school or college district has already been authorized to borrow from past bond measures, or the principal and interest owed from past bond sales that still needs to be repaid, or the projected changes in assessed property valuation and how they affect tax and debt limits, or the past and projected student enrollment? The state does not offer a clearinghouse of information for the public to research and compare data about bond measures and bond debt for educational districts. Much of the information available about debt finance for educational districts is oriented toward interests of bond investors, bond underwriters, bond rating agencies, and the school districts rather than people who pay the debt. In other words, it is straight propaganda, paid with your tax dollars, designed and promoted to hide the truth of the cost of the bonds on society. After all it is “for the children”. Yet, the debt has become so larger that new bonds are doing nothing but paying interest on previously raised bonds. Most of the money does not go toward children. It goes toward management bloat, pensions, hidden investment pools, pet projects, favorite contractors, and kick-backs. The system has morphed into that of Systemic Institutionalized Moral Hazard wherein the guilty claim sovereign immunity from such laws as Ultra Vires which as a law exists for this very purpose. Thus, the courts themselves, although recognizing the fraud, refuse to do anything about it.

See these articles, The Importance of the Vexler Case to Texas and Parallels: Mitch's FOIA Request to Texas OAG vs Dr. Burry's Research on 2008 Mortgage Delinquencies.

Texans who recognize a need for their own local educational districts to refrain from accumulating additional debt have significant obstacles to overcome. State law gives supporters of bond measures a systematic strategic advantage when local districts develop bond measures and put them before voters for approval. Campaigns to support bond measures are funded and even managed by financial and construction industry interests that will profit after passage. And after voters approve a bond measure, educational districts are tempted to take advantage of ambiguities in state law and use bond proceeds for items and activities not typically regarded by the public as construction.

At a time of low interest rates, Texas school and community college districts may benefit in some circumstances from borrowing money to fund school construction, just like households benefit from home mortgages and car loans. But Texas voters — and their elected representatives — need to become much more informed about the debt legacy they are leaving to their children and grandchildren.

Emotional sentiment, lobbying pressure from interest groups, and eagerness to circumvent frustrating tax and debt limits in state law can overwhelm a prudent sense of caution. Irrational decisions that burden future generations cannot necessarily be fixed after the public finds out about them. We are past the point of no return. This will end badly.

[End of Section 1]

Section 2: Why This Article Matters: More Borrowing in 2025

Texans will be asked in 2025 to continue taking on debt for construction of educational facilities, but not a single elected official or a single person running for office, understands the depth of the issue and can articulate the issue to their constituents. There are those who talk, including Governor Abbott but talk is cheap while the interest clock on the debt is growing by the nano-second, which is now considerably more expensive than society can afford. Texans have accumulated compound interest plus annual bond raises for well over 25 years of allowing the state and local educational districts to relentlessly borrow with no checks and balances. The Texas State Comptroller, Texas Attorney General, and Texas Governor have proven less than useless as this is the largest financial issue from which every Texan suffers and will suffer.

That money borrowed through bond sales will have to be paid back — with interest — to the investors who bought them. The property owners who over paid their property taxes based on fraudulent overvaluation are due a sizeable refund or those who committed the crimes of RICO should be jailed. Voters have limited understanding of bonds and how bonds provide funds for construction, and elections focus on what voters will get rather than how they will pay for it. To the detriment of future generations, few Texans realize the huge amount educational districts have been authorized to borrow and the huge amount of debt accumulated.

Section 3: Quantifying and Explaining Texas’s Educational Construction Debt

Whatever voters are asked to approve in 2025 will not launch a new program to fix long-neglected schools to serve a rapidly expanding state population while providing smaller class sizes. That thinking is a legacy of the 1990s that seems to endure today despite 30 years of most bond measures passing at a 55 percent threshold for voter approval, where voter fraud was not committed. Arguments for another state bond measure in 2025 ignore or downplay how local school districts and the state obtained authority in the past 25 years to borrow hundreds of billions for educational construction.

If voters are not told or reminded of recent borrowing patterns, how can they make an informed decision on future borrowing? To rectify the lack of availability of statistics on total bond debt in Texas for educational facility construction, we synthesized and analyzed data regarding Texas educational construction finance. We believe we are the first entity to tie Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, to the Texas Property Tax Code, to the Texas Education Agency, to the Texas Constitution (Uniform and Equal) and to The Constitution of the United States of America. As far as we know, we are the first and only entity to painstakingly research and present an accurate and comprehensive record of the issues facing every single Texas as a result of the Real Estate Tax Fraud and School District Bond Fraud.

Section 4: How Educational Districts Acquire and Manage Debt

It’s likely that most Texas voters have limited familiarity with the organization and governance of their local school districts. When voters authorize their local educational districts to borrow money for construction by selling bonds, presumably they trust that the local school or college district will exercise prudence in managing the process. In today’s world, their trust is betrayed.

To discourage abuse of the school construction finance system, voters need to be aware of how their local government is organized and managed. They also need to realize that state law does not explicitly give Independent Citizens’ Bond Oversight Committees broad authority to review construction programs funded by bond measures.

How can voters become informed about bonds and the process of borrowing money for educational construction through bond sales? Is there a way to explain in clear plain language what actually happens after voters approve of a bond measure and authorize a school or college district to borrow money via bond sales?

Section 5: Capital Appreciation Bonds: Disturbing Repayment Terms

Texas law allows school districts to use an innovative form of debt finance called zero-coupon bonds (among others), also known as Capital Appreciation Bonds. These bonds allow school districts to borrow now for construction and pay it back — with compounded interest — many years later. The borrowing strategy has been a tempting and dangerous lure for elected school boards.

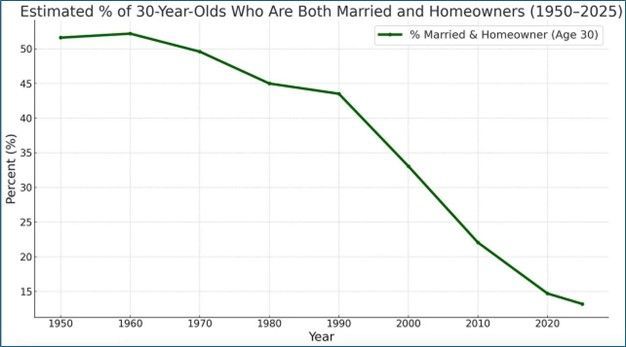

Some people think Capital Appreciation Bonds are a “ticking time bomb” or the “creation of a toxic waste dump.” Others regard critics as uninformed and contend that these debt finance instruments are beneficial for school districts. Since the people who will be paying off many of these Capital Appreciation Bonds are now children or not even born yet, there isn’t much incentive to stop the flow of borrowed money that doesn’t need to be paid back for a generation or two. This is what people think but they could not be more wrong! As we have shown, over 37% of the household population is in harms way of bankruptcy and or losing the roof over their head. We are not living and seeing firsthand how many people (approx. 42,000,000) are suffering via the inflation that has occurred wherein the increase in household revenue could not keep pace with the fraud of inflation – a hidden tax.

Section 6: Tricks of the Trade: Questionable Behavior with Bonds

Some districts are stretching legal definitions to use proceeds from bond sales to pay for items that resemble instructional material more than construction. One example is personal portable electronics such as iPads. Some of the state’s largest districts are purchasing this kind of technology while giving little assurance to the public that long term bonds aren’t the source of the money. This equipment may be obsolete well before the bonds mature, meaning that future generations will pay for these devices long after they are outdated and discarded.

The “interfund” transfers of money from one hidden account to another is an area of further concern. Money being shifted beyond the purview of the public can only be for nefarious purposes.

Section 7: The System Is Skewed to Pass Bond Measures

Considering the advantages that supporters have in preparing and campaigning for a bond measure, perhaps it’s noteworthy that voters reject about 20% of local bond measures for educational construction. At every stage of the process, interests that will benefit from bond sales can take advantage of a system that favors passage of a bond measure. Some issues of concern include use of public funds to develop campaigns to pass bond measures, significant political contributions to campaigns from interests likely to benefit from construction, involvement of college foundations as intermediaries for campaign contributions, and conflicts of interest and alleged pay-to-play contracts.

See the article, Systemic Institutionalized Moral Hazard.

Section 8: More Trouble with Bond Finance for Educational Construction

While compiling the comprehensive information provided in this study, we identified numerous other troubling aspects of bond finance. School districts are evading compliance with the law and making irresponsible decisions. Ordinary voters lack enough data to make an informed vote. Community activists who seek deeper understanding find themselves stymied.

Section 9: Improving Oversight, Accountability, and Fiscal Responsibility

We completely reject the idea that additional oversight and accountability isn’t needed or desirable. There is a famous quote being “We are 9 meals away from civil war”. We have shown that many homeowners cannot afford both a roof over their head and food given the damage caused by inflation. The only solution is to repeal all property tax in favor of the Uniform States Sales Tax.

The Uniform States Sales Tax as outlined in the Bill that Helen Kerwin the Texas State Representative asked me to write, will in addition to paying for municipal requirements, and school district operations and maintenance (O&M) it will put the schools in a position where they can operate without bonds.

See Draft of Proposed Bill to Repeal Real Estate Tax in Favor of Uniform State Sales Tax.

The Uniform State Sales Tax would also apply to funding the following:

- Career technical education facilities to provide job training for many Texans and veterans who face challenges in completing their education and re-entering the workforce. (The history of recent bond measures on the state and local level shows that voters are inclined to support more government spending when veterans are cited as beneficiaries.)

- Upgrade aging facilities to meet current health and safety standards.

- Studies show that 13,000 jobs are created for each $1 billion of state infrastructure investment. These jobs include building and construction trades jobs throughout the state. Influential construction interests are part of the coalition supporting this statewide bond measure. This statement acknowledges their pivotal role in the campaign to pass it.

- Academic goals cannot be achieved without 21st Century school facilities designed to provide improved school technology and teaching facilities. Funds must be directed towards upgrading vocational/career education programs, repairing classrooms and science labs and upgrading technology.

Now let’s review Bonds.

Concern About Debt Growing from State Matching Grants for Local Educational Districts

Increase Tools for Local Control: Expand Local Funding Capacity

While school districts can pass local bonds with 55% percent approval, assessed valuation caps for specific bond measures and total caps on local bonded indebtedness are completely ignored by the Attorney General who is the sole signator to ensure that money is available to pay the bonds off. No school district should have access to the bond market until all current bonds are brought down to no more than 2% of the effective gross income for any homeowner and no more than 1% of the effective gross income for any income property under a worse case scenario. The appropriate goal given the crimes committed against the public and allowed to continue and expand is to force every school district to operate on a cash basis from local funds meaning no state and no federal funding which is why the repeal all property tax Uniform States Sales Tax is the only solution.

What Are “General Obligation Bonds” Referenced in Ballot Language for Bond Measures?

Corporations and state and local governments issue bonds to raise money. Bonds sold by local governments are called municipal bonds. An appealing aspect of many municipal bonds for investors is their tax-exempt status.

Municipal bonds such as those sold by Texas school districts for construction are called general obligation bonds, meaning they are backed by the “full faith and credit” of the districts. These districts theoretically have legislative power to collect enough money through property taxes, other borrowing, selling assets, or other sources of revenue to fulfill their obligation to make payments on the bonds when due. Those taxes are collected from property owners in the district. (Revenue bonds are another kind of municipal bond, paid off through tolls, lease payments, user fees, or other service payments.) The problem is now that there is no such thing as “full faith and credit of the districts” as the majority of school districts are bankrupt.

Comparing Current Interest Bonds to Capital Appreciation Bonds

When voters are asked at an election to approve a bond measure to pay for construction at a school district or community college district, they generally have been told that a “Yes” vote will authorize the sale of general obligation bonds to fund that construction.

Texas educational districts are issuing two kinds of general obligation bonds: Current Interest Bonds and Capital Appreciation Bonds. Usually, the district does not tell voters what kind of general obligation bonds it will sell, unless it specifically passes a resolution before the election stating it will not sell Capital Appreciation Bonds and includes that condition in the ballot statement.

1. Current Interest Bonds (also called Fixed Rate Bonds)

These are the “traditional” kind of municipal bonds. A buyer of Current Interest Bonds gets a periodic interest payment (usually semi-annually). When the bond matures, the buyer gets the principal back.

2. Capital Appreciation Bonds (also called Zero Coupon Bonds)

A buyer of Capital Appreciation Bonds does not receive semiannual or other periodic interest payments. Instead, the buyer receives all of the interest – compounded over the length of maturity for the bond – together with the principal when the bond matures. There is no regular payment of interest, but the accumulated (“accreted”) interest is compounded over many years, making the wait a worthwhile investment. Capital Appreciation Bonds are purchased at a deeply discounted amount from their face value.

Two Costs to Educational Districts of Borrowing Money Via Bonds

From the perspective of the school district, the additional financial cost of borrowing money by selling bonds as opposed to spending money from the district general fund results from (1) interest and (2) transaction fees.

Interest

If someone borrows $1000 for five years from a lender at an annual interest rate of 5 percent, the borrower and the lender agree that the borrower will pay back the $1000 over five years and also pay 5% of that $1000 ($50) multiplied by five years for a total of $1250. The borrower gets the $1000 immediately to use, and the lender earns annual interest income of $50 over five years for a total of $250. Both parties consider themselves to get a benefit from the transaction.

Likewise, if a school district issues a traditional $1000 Current Interest Bond at an annual interest rate of 5 percent with a five-year term of maturity and an investor buys the bond at its face value of $1000, the school district gets the $1000 immediately to use for construction, and the investor earns annual interest income of $50 over five years for a total of $250. When the five years are over, the investor gets the $1000 back. Both parties get a benefit from the transaction. In addition, the investor does not have to pay taxes on the interest income for certain types of municipal bonds.

School districts usually sell series of bonds as a package with different maturities and interest rates.

Transaction Fees (Issuance Fees)

Bond buyers are not the only party to make money from bonds issued by Texas school districts. Similar to taking out a mortgage, a variety of parties in the financial services industry are involved in the preparation and sale of bonds, and each party gets a fee for participating in the transaction. These fees are classified as “costs of issuance.”

To prevent these fees from cutting into the amount of money authorized by voters for construction, educational districts routinely inflate the interest rates on bonds they sell so that the price is higher than the face value of the bond. After the bonds are sold, that extra money, or “premium,” is used to pay the costs of issuance.

How are Municipal Bonds Bought and Sold? Who Buys Them?

Municipal bonds are not traded on an exchange like stocks. Instead, investors buy and sell bonds “over the counter” through dealers and brokers registered with the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), a self-regulatory organization overseen by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. These dealers and brokers act as underwriters or intermediaries between issuers and investors. They charge fees, or “mark-ups” for the transactions.

Once a school district sells a bond, the bond can be traded in the municipal bond market. The price will fluctuate and investors will be concerned about yield — the amount of income earned as prices rise and fall.

According to Federal Reserve statistics, individual investors hold a little more than two-thirds of municipal bonds, about 42 percent directly and about 28 percent through mutual funds and other investment vehicles. Major institutional investors include asset management firms, insurance companies, and commercial banks.

One of the arguments to cap or eliminate the federal tax exemption for income from municipal bonds is that the exemption mainly benefits wealthy individuals who buy bonds as a tax-exempt investment. Buyers of municipal bonds do not generally “keep the money in the community” because they aren’t in the community. And they generally do not buy bonds issued by educational districts to “help the children” or “provide vocational training to veterans.” They buy them to make money.

Ironically, the same Progressive activists who call for higher taxes on the rich also tend to support educational bond measures that help the rich to earn investment income that is tax-free. Forcing the rich to pay taxes on income earned through municipal bonds could collapse the demand for these bonds and make borrowing money for construction a much more expensive proposition for school and college districts.

How Does an Educational District Pay Back the Borrowed Principal Plus Interest on Bond Sales?

People pay back the principal and interest on car loans, school loans, and mortgages using their income. Educational districts pay back the principal and interest on bonds using their “income,” that is, taxes collected from property owners in the district.

In many places, after a school district or community college district borrows money by selling bonds for construction, it informs the county auditor and county treasurer/tax collector. Based on the assessments of property value determined by the county assessor, the county treasurer calculates the appropriate tax rate and generates individual tax bills for owners of property such as houses, farms, apartment buildings, commercial buildings, manufacturing facilities, business infrastructure, and undeveloped land. A specific rate and tax for each bond measure is listed on the tax bill.

In most places in Texas, it is the Central Appraisal District (CAD) that sets the property values, issuing a Notice of Appraisal and facilitating a protest process. The CAD later provides the certified market values or net appraised value to the County Assessor-Collector who then issues the property tax bill and collects the tax. Both the CAD and the Assessor-Collector work on behalf of the taxing entities, i.e. cities, schools, county, special districts, etc., etc. The taxing entities of a property are listed on the Notice of Appraisal provided by the CAD and on the Property Tax Bill produced by the Tax Assessor-Collector, with no specific information provided on either of these documents regarding how much of the tax is related to bonds issued.

These taxes are called ad valorem taxes. Ad valorem is Latin for “according to worth” and indicates that taxes are levied (imposed) on property owners in proportion to the assessed value of their property.

Does Renting or Leasing Mean That You Don’t Pay for Educational Construction or the Cost of Borrowing Money for It?

Households that rent property or businesses that lease property do not pay property taxes directly. However, it is not true to claim or think that renters or lessees don’t have to pay for educational construction and the costs of borrowing money to pay for that educational construction. Property owners can and do incorporate the cost of their property taxes into their rents or leases. Bond sales by a school or college district may result in higher rent.

Technical Definitions of Bonds

Notice that the common term in all of these definitions is debt. When a school or college district sells bonds, it borrows money from investors and must pay them the money back over time, with interest.

Sources

- “Statement on Making the Municipal Securities Market More Transparent, Liquid, and Fair,,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, February 13, 2015, accessed June 28, 2015, www.sec.gov/news/statement/making-municipal-securities-market-more-transparent-liquid-fair.html

- “Letters to Congress/Administration,” National Association of Bond Lawyers, accessed June 28, 2015

- The Bond Buyer www.bondbuyer.com

Explaining and Contrasting Current Interest Bonds and Capital Appreciation Bonds

The traditional Current Interest Bonds (also called Fixed Rate Bonds) are relatively easy to understand. If someone buys a Current Interest Bond and holds it until it matures (reaches the end of its time period for borrowing), that buyer receives interest on a regular basis (usually semi-annually). The buyer gets the original principal paid back when the bond reaches the end of its term of maturity.

Here’s an example of how a Current Interest Bond works:

- An entity buys a $1000 Current Interest Bond issued by a school district at face value (also known as par value) with a 25-year term to maturity at a 2.5 percent interest rate.

- Each year, for 25 years, the buyer gets $25 in interest from the school district, because 2.5% of $1000 is $25.

- When the bond matures, the buyer gets the principal of $1000 back from the school district.

- The total interest earned over 25 years is $625, because $25 times 25 is $625.

- Although the $625 is income, the buyer will never have to pay tax on that interest if the bond is tax-exempt, as is typical with municipal bonds.

Obviously the school district must levy taxes on property owners each year throughout the 25-year term to maturity so that it has enough money to pay interest each year (and ultimately pay back the principal at the maturity date).

Capital Appreciation Bonds (also called Zero Coupon Bonds) are more difficult to understand. Someone who buys a Capital Appreciation Bond pays for it at a price deeply discounted from the face value (par value) of the bond. The buyer does not receive interest payments until the bond reaches maturity, at which point the buyer is paid the face value of the bond, which is the deeply-discounted price (the principal) plus all of the interest earned during the term to maturity.

During the term to maturity period of the Capital Appreciation Bond, interest accumulates over time. The interest is compounded, meaning interest for a time period is earned on the original amount of money and also earned on any of the interest that has already been accumulated up to that time period.

Compound interest that accumulates as a Capital Appreciation Bond grows in value is called “accreted interest.” “Accreted” (a word derived from the Latin accrescere, to increase) means accumulated over time.

Here’s an example of how a Capital Appreciation Bond works:

- An entity buys a $5000 Capital Appreciation Bond with a 25-year term to maturity at an interest rate of 5 percent.

- The discounted price of the bond is $1477.

- When the bond matures, the buyer gets $5000 back from the school district.

- The total earned over 25 years is $3,523.

- Although the $3,523 is income, the buyer will never have to pay tax on that interest if the bond is tax-exempt, as is typical with municipal bonds.

The school district benefits because for many years it does not need to levy taxes on property owners in order to make interest payments. It can borrow much more money through bond sales without being restricted by tax and debt limits established in state law. The community can enjoy the benefits of the bond sales without having to pay for them — at least for a while.

And although the buyer does not get a regular interest payment, the accumulated (“accreted”) interest is compounded over many years, making the wait a worthwhile investment. The cliché about “the power of compound interest” for an investor is accurate.

Why Did Capital Appreciation Bonds Become Popular?

The public first became aware of Capital Appreciation Bonds in 2012 when news media reported on a 2011 debt financing arrangement at the Poway Unified School District. Most reports insinuated that limits on taxes and debt established by the legislature in 2000 in conjunction with Proposition 39 had forced schools and community colleges to borrow money by selling Capital Appreciation Bonds. Allegedly these limits were constraining school and college districts from implementing necessary construction programs at a time of plummeting property values. Educational districts saw Capital Appreciation Bonds as the only debt financing option available to alleviate school overcrowding and ensure children’s safety.

But in reality, Capital Appreciation Bonds have been a component of bond issues by Texas educational districts for over thirty years.

Capital Appreciation Bond Origins

The first sentence in a 1982 article in the New York Times declared, “Give Wall Street a headache like double-digit interest rates, and someone will invent an aspirin like the zero-coupon bond.” According to this article, in 1981 J.C. Penney became the first corporation to issue Capital Appreciation Bonds. In 1982, E.F. Hutton became the first bond broker to underwrite Capital Appreciation Bonds for municipal governments.

A survey of news coverage on Capital Appreciation Bonds during the 1980s reveals that the focus of journalistic concern for this new form of municipal debt finance was the risk to investors. Needless to say, Capital Appreciation Bonds endured past the era of high interest rates, and the aspirin for investors became a headache for taxpayers.

Who Buys Capital Appreciation Bonds?

Capital Appreciation Bonds are not necessarily a wise decision for an investor, so who sees an investment advantage in buying them? James Estes, Professor of Finance at California State University, San Bernardino tried to answer this question and reported the results of his investigation in a 2013 paper. After observing that Charles Schwab & Co, Inc. does not offer or sell Capital Appreciation Bonds, he contacted twelve companies that offer municipal bond funds. All twelve claimed they don’t market funds featuring Capital Appreciation Bonds. Company representatives told Estes that Capital Appreciation Bonds were undesirable to their investors because of their lack of current interest payments, their poor yield, and their high risk.

Estes also investigated rumors on the web that CalPERS might be holding many municipal Capital Appreciation Bonds. CalPERS spokesperson Danny Brown denied that CalPERS holds them and cited their risk. Finally, Estes mentions the claim of a finance reporter that international banks hold Capital Appreciation Bonds in a trust administered by Bank of America.

In response to a Twitter inquiry from the author of this report, a former reporter for Voice of San Diego tweeted that he never learned who held the district’s Capital Appreciation Bonds during his 2½ years reporting on Poway Unified School District’s Capital Appreciation Bond fiasco: “The word was that the debt had likely been sold and resold and resold. Also no repository for that info…I always wanted to know.”

In 2014, a municipal bond advisor named Dale Scott of Dale Scott & Company presented a plan to Poway Unified School District for the district to buy back some of its Capital Appreciation Bonds using funds from a property tax increase. One challenge for this district is identifying who owns the bonds so offers can be made to buy them back. Scott pointed out that he had managed to find owners of Capital Appreciation Bonds issued by the Stockton Unified School District and buy back about 30 percent of them. According to an August 20, 2014 article in the San Diego Union-Tribune, “Scott said there is a myth that capital appreciation bonds are impossible to acquire once they are sold, but the reality is the bond holder may have many reasons for selling bonds that may take decades to mature.”

Tax and Debt Limits Make Funding of Construction Programs Highly Dependent on Assessed Property Valuation

Because tax and debt limits are based on annual assessed property valuation in a district, the limits change yearly as a reflection of the real estate market. If property values increase compared to the previous year, the amount of money that can be borrowed increases relative to the previous year. If property values decline compared to the previous year, the amount of money that can be borrowed that year decreases. Educational districts hope (and usually project) property value to increase at a respectable rate for many years to come.

If the substantial increase in home prices during the mid-2000s gave school and college districts several years to borrow a lot more than perhaps originally anticipated, the dramatic drop in the following years hindered school and college districts, especially those with ongoing construction programs. From 2007 to 2011, assessed property valuation in some regions of Texas declined by as much as 50%, especially in exurban areas of Texas that grew rapidly in population during the 2000s as young families sought home ownership at prices they could afford.

Not surprisingly, these same regions needed new school construction to accommodate the children in these young families. Because of tax and debt limits, educational districts could not raise tax rates or borrow more money using traditional Current Interest Bonds to compensate for the loss in revenue resulting from the decline in property values.

Capital Appreciation Bonds are a clever way to circumvent the debt limits. A school or college district can take on a long-term debt obligation of $5000 by selling a bond but declare the debt to be $1300 because the bond was sold at the deeply discounted “principal” of $1300. And by deferring payment to bond investors until the bonds mature, the district can borrow money without exceeding the tax limit.

Hoping for the Best with Capital Appreciation Bonds

Of course, school districts will eventually have to collect a lot of money through levying taxes on property owners to pay principal and accreted interest to the buyers of Capital Appreciation Bonds. Essentially, Capital Appreciation Bonds represent a district’s gamble that assessed values will climb rapidly enough to produce sufficient tax revenue to allow issuers to pay off the bonds when they become due. If the anticipated increase in assessed property valuation fails to occur during the term of maturity, the district cannot pay principal and interest owed in future years.

There is little political disincentive for elected board members to borrow money today for school construction and impose a commitment on future generations to pay it off in 25, 30, or even 40 years. Only the elected board members of the Poway Unified School District have suffered political consequences from approving this kind of debt finance. But future school and college board members (who are children today) may be unjustly subjected to voter ire when the bill on Capital Appreciation Bonds is finally due.

Backers of Capital Appreciation Bonds Stubbornly Defend Them

Throughout the state, elected district officials and administrators defended their decisions to sell Capital Appreciation Bonds. Their response to criticism was common and consistent:

- Voters wanted school construction done as soon as possible.

- Capital Appreciation Bonds were the only way available to get the money.

- We didn’t do anything wrong.

- Look at the complete program instead of focusing on individual bond issues.

These claims generally echoed the arguments of parties involved in the preparation and sale of those bonds. These bond experts knew the obscure and complicated business of municipal bonds, but they also had a financial interest in seeing these bond sales continue.

Sources

- “Market Place; Zero-Coupon Municipals,” New York Times, March 21, 1982, accessed June 28, 2015, www.nytimes.com/1982/03/31/business/market-place-zero-coupon-municipals.html

- “Capital Appreciation Bonds: The Creation of a Toxic Waste Dump in Our Schools,” Alpha Wealth Management, April 11, 2013, accessed June 28, 2015, www.alpha-wealth.com/resources/publications/CAB-Paper.pdf

Tricks of the Trade: Questionable Behavior with Bonds

The System Is Skewed to Pass Bond Measures.

Considering the advantages that supporters have in preparing and campaigning for a bond measure, perhaps it’s noteworthy that voters reject about 20% of local bond measures for educational construction. At every stage of the process, interests that will benefit from bond sales can take advantage of a system that favors passage of a bond measure. Some issues of concern include use of public funds to develop campaigns to pass bond measures, significant political contributions to campaigns from interests likely to benefit from construction, involvement of college foundations as intermediaries for campaign contributions, and conflicts of interest and alleged pay-to-play contracts.

It’s Not “Tough” Anymore to Pass Local Bond Measures for School Districts

An industry of campaign consultants helps educational districts to convince voters to approve bond measures. They have developed a formula that generally results in victory. Here are some of the most obvious tactics used to achieve that success rate of 80 percent.

Using Public Funds to Hire a Consultant for Voter Research That Is Subsequently Useful in the Election Campaign to Pass the Bond Measure

Many Californians would be astonished to learn that school and community college districts can use funds from their operating budget to develop a strategy to pass a bond measure. Yet this practice is common.

California law prohibits community college districts and K-12 school districts from using public funds or resources to campaign in support or opposition to bond measures. Education Code Section 7054 states “No school district or community college district funds, services, supplies, or equipment shall be used for the purpose of urging the support or defeat of any ballot measure…”

However, these same public resources CAN be used to provide information to the public about the possible effects of any bond issue or other ballot measure, as long as that information constitutes a fair and impartial presentation of relevant facts to aid the electorate in reaching an informed judgment regarding the bond issue or ballot measure.

A 2005 opinion from California Attorney General Bill Lockyer confirmed that it is legal for a college district (and a school district) to use district funds to hire a consultant to conduct surveys and establish focus groups to assess the following important conditions for a campaign:

- The potential support and opposition to a bond measure, by gathering information and evaluating the potential for the adoption of a bond measure by the electorate.

- The public’s awareness of the district’s financial needs.

- The overall feasibility of developing a bond measure that could win voter approval.

According to the Attorney General, this is not “partisan campaigning.”

Of course, this professional research and analysis — paid for by taxpayers — puts a school or college district at a significant advantage for a bond measure campaign. Consultants determine which words and arguments are most effective in motivating various demographic groups in the district to vote for a bond measure. Consultants also determine which arguments would be most effective for opponents of a bond measure and how the school district can neutralize those arguments.

Further research is needed to reveal how often a “feasibility study” concludes that a bond measure is not “feasible.” Considering that the firm evaluating the feasibility of a bond measure may often be seeking future contracts with the district or the campaign committee, there may be a conscious or subconscious inclination to manipulate the survey questions or the results to obtain a deceptively positive recommendation. In his book Win Win: An Insider’s Guide to School Bonds, Dale Scott of Dale Scott & Company cites a case in which he suspects a consulting firm had self-interested motivations when it recommended that a school board place a bond measure on a June primary ballot rather than a November presidential ballot with an apparent better chance of passage. Voters rejected the bond measure.

Considering that voters approve about 80% of educational bond measures at the 55% voter approval threshold, cynics would argue the real purpose of surveys isn’t to determine “feasibility” but to use public funds to develop election campaign strategy. Based on promotional material of firms that specialize in feasibility studies for bond measures, the argument is valid.

Here’s an excerpt from a consulting firm’s website about how information from taxpayer-funded surveys can be used to improve the chance of election victory:

…an initial baseline survey can determine the overall feasibility and voter acceptance of a bond or parcel tax measure at different funding levels. It can test how voters respond to different versions of the ballot title and summary, and – through analysis of respondent demographics and past voting patterns – it can help determine which election calendar promises the greatest likelihood of success. The same survey can also determine the effectiveness of the rationales and arguments that might be offered for and against a bond or parcel tax measure, thus helping shape the communications themes that will explain how the measure addresses voters’ concerns… works with its clients to perfect ballot language and voter pamphlet arguments, using our empirical data to guide our advice.

A second example:

Public opinion research is critical to packaging a revenue measure for success. School districts can maximize the dollars that they raise through general obligation bonds, Proposition 39 bonds, and parcel taxes by collecting pertinent voter opinion data and using this information to solicit support. can help maximize your measure’s potential by providing accurate and reliable results…We provide both qualitative and quantitative research services in the following areas:

- Assessing baseline support for revenue measures

- Identifying the highest achievable tax threshold and total bond amounts

- Determining the arguments and features of the measure that will increase support

- Evaluating the need and content for a public information campaign

- Determining the best election in which to place the measure on the ballot

- Packaging a measure for success

A third example:

The California Policy Center (CPC) understands that the research can be the first step not only in determining the feasibility of a potential revenue measure, but also in bringing together the various stakeholders and constituencies that will need to be involved and supportive in order for any ballot measure to be successful. We know that the issues facing the District do not exist in a vacuum and must be put into the context of the current political and cultural environment in the District. The voter opinion survey presents the District with an opportunity to hear from the administration, teachers, staff, Board, and other community stakeholders about their priorities. Involving key stakeholders in the research design leads to confidence in the research findings and helps ensure that the parties who are integral to a ballot measure’s success are on board and on the same page.

Even items scheduled on board meeting agendas to hire the consultant and then to review the survey results create a positive news opportunity for bond measure proponents. At this early stage in the process, potential opponents usually have not emerged to present a different perspective. And a finding of measurable strong support portrays a bond measure as something already broadly supported by community, thus convincing undecided individuals and organizations that the bond measure is worthy of support and discouraging individuals and organizations that might be inclined to oppose it.

Public Resources Used to Win a Bond Measure

A consulting firm for school bond measures has developed a “Finance Measure Checklist for Success” that outlines five steps for victory. A school district can fund and coordinate four of the five steps with public resources. Only the fifth and final step requires the district to “step away” from explicit political campaigning and pass primary responsibility to a separate political entity, such as a Political Action Committee.

By the time the “partisan campaign” begins, the community college district or K-12 school district has spent a year or longer obtaining polling data, alerting voters directly and through the news media to the need for school construction, and refining campaign themes and messages. A taxpayer-funded effort to pass it has been well underway, without a cent of money raised or spent by a campaign committee. Already the proponents have an advantage over any opposition to the bond measure.

Comparing the Election Campaigns of Supporters and Opponents

There is an existing network of professional political consultants who are experienced in establishing a campaign committee, collecting corporate campaign contributions, and communicating with voters using an effective message developed from the results of the district’s feasibility study. Political campaigning is a business, and fierce competition forces consulting firms to build and maintain a reputation for winning. Meanwhile, professional campaign vendors are ready to design, print, and mail campaign material. Endorsements can be quickly obtained from political, business, and community leaders. Participants in phone banks and precinct walkers can be recruited and even paid if a financial incentive is necessary.

In addition, potential district contractors are able to promote school bond measures throughout Texas including county offices, private sector businesses, architects, attorneys, consultants, construction managers, financial institutions, modular building manufacturers, contractors, developers, and others that are in the school facilities industry.

Contrast this to the typical opposition to a bond measure. Often there aren’t any formal opponents. Sometimes the opposition consists of a few individuals known in the community as gadflies or anti-tax or libertarian activists. Opposition can gain more credibility if there is an existing local community or taxpayer organization that provides a formal forum for fiscal critics to meet and strategize. That organization is almost always more effective if it employs full-time professional staff responsible to a board of directors.

In rare cases there is a well-funded opposition campaign backed by local business leaders and interest groups and run by professional political consultants.

Potential opponents must regularly monitor local news sources and the meeting agendas of local educational districts to know when an elected governing board is considering a bond measure and passes a resolution putting a bond measure on the ballot. Sometimes the board does this immediately before the legal deadline, thus providing very little time for opponents to respond before the election.

Concerned parties must meet to consider the bond measure and determine an appropriate position. Someone needs to know or obtain the various laws concerning the submission of an opposing argument in the ballot pamphlet, and someone needs to write the opposing argument and go through the process of getting group approval of the text. It needs to be submitted on time and in compliance with often technical legal requirements. A few people in the organization must volunteer to write commentaries or letters to the editor of the local newspaper and then follow through with the promise. Some people may chip in some money from their small businesses or personal savings to order some lawn signs, which have to be designed, approved, printed, and distributed.

Nonetheless, bond measures do fail almost 20% of the time despite the organizational and financial advantages of supporters. A 2003 report from the Public Policy Institute of California noted that big urban school districts in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Los Angeles area with high numbers of registered Democrat voters tended to propose more bond measures and win voter approval of those bond measures more often that smaller districts in rural areas, such as the Central Valley. This pattern appears to continue.

In some large urban school districts in California, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, bond measures always win easily and opposition seems futile. As long as these districts don’t propose bonds too frequently, they rarely have to worry about opposition.

Top Donors Are Current or Potential Contractors for Finance and Construction

Generally, the public has poor access to records concerning the contributions to and expenditures of campaigns to pass bond measures. In some counties the campaign forms must be obtained in person and are provided as photocopies. Other counties have electronic databases that simply link to scanned documents. Trying to compile or analyze campaign finance patterns would be a tedious undertaking.

Nevertheless, compilations of contributors to four campaigns to pass five bond measures in November 2012 suggest that what is commonly assumed is accurate: these campaigns are mostly funded by companies likely to earn money from the proceeds of those bond sales.

Community College Foundations Entangled in Controversy

A 2005 opinion of the California Attorney General (also referenced above in relation to bond underwriters and campaigns) determined that a community college district’s auxiliary organizations (such as foundations and student body associations) are legally able to contribute their own privately raised funds to a political action committee established specifically to advocate voter approval of a bond measure. It is routine to see community college foundations contributing to bond campaigns. Like any 501(c)3 non-profit, college foundations are permitted to spend up to 20% of expenditures for influencing legislation, and that includes bond measures.

Controversy arose about this practice in 2004 after the Sierra College Foundation contributed about $100,000 to three bond measure campaigns for the Sierra Community College District. Neither the Political Action Committees nor the Sierra College Foundation reported the contributions to the California Fair Political Practices Commission.

At least two board members alleged that the college president, who estimated making 40 presentations to groups of prospective donors, had tried to hide the identities of contributors to the bond measure campaigns (including architects and engineering firms) using the Foundation as an intermediary. These board members also believed that people interested in contributing to the bond campaign were advised to make their contributions to the Foundation instead of the bond measure campaign committee in order to benefit from a tax deduction. The Placer County Civil Grand Jury ended up concluding there wasn’t any reliable evidence to support these accusations against the college president, but the incident exposed some of the potential problems with college foundations acting as a intermediary to fund campaigns to pass bond measures.

Alleged “Pay-to-Play” by Some Bond Underwriters Gets Attention

In the spring of 2012, there was a flurry of news media attention about some bond underwriters making contributions to campaigns for bond measures and subsequently making money through issuance fees as the underwriter for the bond sales. The news article that broke the story reported the following:

Leading financial firms over the past five years donated $1.8 million to successful school bond measures in California, and in almost every instance, school district officials hired those same underwriters to sell the bonds for a profit, a California Watch review has found. The practice is especially pronounced in California, where underwriters gave 155 political contributions since 2007 to successful bond campaigns for school construction and repairs.

Under an amendment to Rule G-37, adopted in 2010, the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) requires each broker, dealer or municipal securities dealer to send a form quarterly to the MSRB reporting their contributions to bond ballot campaigns if those contributions exceeded $250. These contributions do not prohibit brokers from doing business with the entity proposing the bond measure, but the reporting requirements allow the public to identify these contributions as part of any effort to cross-reference them with contracts. Other rules prohibit brokers from doing business with entities if they have made campaign contributions to entity officials who make decisions related to selecting brokers for bond issues.

In 2009, the MSRB considered toughening Rule G-37 to prohibit brokers from doing business with government entities if those brokers contributed to campaigns to pass bond measures proposed by those government entities. California was cited as a particularly notorious location for the appearance of “pay-to-play” relationships. In the end, the MSRB declined to change the rule, citing constitutional First Amendment concerns.

The Bond Buyer reviewed broker contributions to 2010 campaigns to pass bond measures in California and identified “a nearly perfect correlation between broker-dealer contributions to California school bond efforts in 2010 and their underwriting subsequent bond sales.” A spokesperson for California State Treasurer Bill Lockyer responded to the review: “…it is probably time to end the days when underwriters, bond counsels or financial advisors fund, manage or provide other key support for local bond campaigns, then get paid to do work on the bond sales.” In 2013, the Los Angeles County Treasurer and Tax Collector Mark Saladino adopted “a complete ban on cash and in-kind contributions from all firms in our underwriter pool starting no later than when we renew our pool for another year in January 2014.”

Sources

- “Opinion No. 04-211,” Legal Opinions of the Attorney General, April 5, 2011, accessed June 28, 2015, oag.ca.gov/system/files/opinions/pdfs/04-211.pdf

- “Public Opinion Research for Today’s School Districts,” Godbe Research, accessed June 28, 2015, www.godberesearch.com/level2/pdf/School_BR_2006.pdf

More Trouble with Bond Finance for Educational Construction

While compiling the comprehensive information provided in this study, California Policy Center researchers identified numerous other troubling aspects of bond finance. School and college districts are evading compliance with the law and making irresponsible decisions. Ordinary voters lack enough data to make an informed vote. Community activists who seek deeper understanding find themselves stymied. Just like Texas!

Bad Government Behavior – Who is worse…California or Texas? It is clear via this article that the pattern and practice of conspiracy to defraud is one in the same. The Chief Appraisers just like the School District Superintendents take classes together to teach each other what they are doing. The law does not matter to them.

1. Some School and College Districts Don’t Comply with Proposition 39

Two examples of investigative reports on educational district compliance with Proposition 39 are the San Diego County Taxpayers Association 2015 School Bond Transparency Scorecard and a 2010 San Mateo County Civil Grand Jury report entitled “School Bond Citizens’ Oversight Committees, Prop 39.” These reports show some districts are close to full compliance while others don’t seem to be complying at all. It appears that two types of districts are broadly failing to comply: (1) small school districts, which may have limited capability to comply, and (2) large school districts routinely accused of fiscal irresponsibility and mismanagement.

2. Spend It Or Lose It? Districts Can Sell Bonds Decades After Voter Approval

Some school and college districts ask voters to approve new authority to borrow additional money for facilities construction even though much of the authority from previous bond measures to borrow money has not been used. This is a strategy to circumvent tax and debt limits imposed by state law on individual bond measures, and it leaves millions (and sometimes billions) of dollars in borrowing authority dangling for future school boards to exercise long after voters have forgotten the election.

3. Districts Sell Bonds at a Premium and Use the Extra Money to Pay Fees Related to Selling the Bonds

The California Attorney General’s office is preparing a legal opinion (14-202) on whether school and college districts can use a premium to pay bond issuance fees. The question asked is “May the ‘premium’ generated from a school district bond sale be used to pay for expenses of issuance and other transaction costs?” (See Table 8 for a list of such fees.)

In 2011, the California Attorney General warned the Poway Unified School District that “artificially inflating the interest rate to generate premium” to pay for costs of issuance would be illegal.

The California State Treasurer or a state agency needs to compile a list of bond issues for which buyers paid a premium that the district then used to pay bond issuance fees. How rampant is the practice and how much has it cost California taxpayers?

4. Firms Get Contracts to Prepare a Bond Measure Before the Election and Then Get Contracts to Implement the Bond Measure After the Election

The California Attorney General’s office is preparing a legal opinion (13-304) on whether a party that gets a contract with a school or college district for surveying voters and preparing a bond measure can then get a contract as the bond underwriter (bond broker) for issuances approved by that same bond measure. The question asked is “In connection with a school or community college bond measure, does a district violate state law by contracting with a bond underwriter for both pre-election campaign services and post-election underwriting services?”

5. Is There Exaggeration, Deception, or Outright Fraud When Districts Assess Needs for Another Bond Measure?

Some school and college districts seek to borrow more money for school construction even when their enrollment has been substantially declining for years and is projected to continue declining. Overcrowding would not seem to be a problem in such districts. Is the need legitimate?

A state agency should conduct random audits for several school or college districts to determine the credibility of their facilities plan based on their evaluations of safety, class size reduction and information technology needs. Numerous bond measures include the words “safety” and “security” in the ballot question and statement, insinuating to voters that students and teachers may be physically harmed unless the district can borrow money via bond sales for construction projects. Are there truly legitimate threats to safety and security in schools throughout the state?

6. A Handful of Voters in Future Development Areas Have Given School Districts Massive Authority to Sell Bonds and Put the Bills on Future Residents

When researchers for the California Policy Center developed preliminary charts now in the appendix to this report and began circulating them publicly early in 2015, two bond measures received unexpected attention on the list of 1,147 considered since enactment of Proposition 39.

In both of these cases, a school district created the boundaries of a School Facilities Improvement District — carved out of the entire district — in a sparsely-populated where future development will occur and future schools will be built.

Apparently the Folsom-Cordova Unified School District compared this option to the establishment of a Community Facilities District funded by Mello-Roos fees and chose this financing option. Its Improvement District had a population in 2006 of about 330 persons.

Shortcomings That Hinder Voters

The California legislature recognizes that some ballot statements for bond measures do not contain enough relevant information for voters. In 2014, Governor Brown signed into law Assembly Bill 2551, introduced by Assemblyman Scott Wilk, which requires each bond issue proposed by a local government to include estimates from official sources of tax rates for certain years, the maximum annual tax rate, and total debt service (the principal and interest that would be required to be repaid if all the bonds are issued and sold). The bill never received a vote in opposition. In 2015, Assemblyman Jay Obernolte introduced Assembly Bill 809, which requires the ballot statement for local tax measures to include information on the amount of money to be raised annually and the rate and duration of the tax to be levied. As of July 13, 2015, the bill was moving through Senate committees after passing the Assembly 57-8 (with 15 not voting).

1. Ballot Questions and Statements Aren’t Useful to the Ordinary Voter

A 2009 Little Hoover Commission report on bond measures noticed the lack of “fundamental criteria for ballot measures” and recommended a “simple, easy-to-understand report card in the voter guide for all bond measures placed on the ballot.” The problem continues unabated today.

Bond measures tend to be presented to voters in a vacuum, with minimal context about the past history of the district’s bond measures and construction programs. Voters can misinterpret proposed bond measures as a desperate response to a long-standing unaddressed crisis of unsafe, decrepit, and overcrowded classrooms, laboratories, and athletic facilities.

Voters need a chance to consider whether they should approve millions or even billions in new bond authority, even if millions or even billions of money has already been borrowed and millions or billions in existing authority still remains to be spent. This would reveal any history of foolish bond issues or debt acquisition.

2. Information Provided to Voters Needs More Pictures, Charts, and Tables

As mentioned in Section 5 of this report, a possible reason why the public finally discovered the extreme Capital Appreciation Bond financing arrangements of the Poway Unified School District was the simple and colorful graphics in the Voice of San Diego articles about it. More than ever, American society depends on imagery, charts, and tables for information instead of prose.

3. Voters Need to See the Importance of Assessed Property Valuation and District Enrollment Projections

Projections of the rate of change for assessed property valuation in the district should be among the most important elements in decisions concerning bond issues. Voters need to consider a history of wild swings in assessed property valuation in the district and decide whether projections are realistic, exaggerated or pure fraud.

A report on Capital Appreciation Bonds from the 2013-2014 Orange County Grand Jury recognized “there has been virtually no publicity concerning the implications of debt service repayment for CABs, specifically the magnitude of potentially higher taxes. There is potential for some school districts, through the County, to increase property taxes well beyond what was presented when the bonds were issued in order to repay the CABs.” Results of the Grand Jury’s investigation were depicted in tables. At least three school districts in Orange County predicted assessed property valuation to grow at unrealistically high rates when they asked voters to approve bond measures. As a result, these districts will have to levy tax rates far beyond what was portrayed to voters in order to pay off the Capital Appreciation Bonds.

In addition, voters need to be aware if the school or college district asking to borrow money for construction is experiencing a long-term trend up or down in student enrollment. There are arguments for borrowing a lot of money for facilities construction during a time of dropping enrollment (Wiseburn Unified School District is an example of this deliberate strategy), but the message to voters needs to reflect actual circumstances.

4. Ballot Questions for Bond Measures Deceive and Manipulate Voters

Several ballot questions for proposed community college bond measures have specifically singled out veterans as beneficiaries. As noted in Section 2, polling shows that voters respond positively to the idea that a bond measure will help veterans. As a result, the possibility that veterans will be using facilities funded by bond proceeds gets prominent mention in ballot language.

On June 29, 2015, the Solano County Grand Jury issued a report highly critical of the ballot title and ballot statement for Measure Q, a November 2012 ballot measure that authorized the Solano Community College District to borrow $348 million for construction by selling bonds to investors. The Grand Jury asserted that voters were duped into thinking that proceeds from selling bonds would directly provide classroom instruction and job training for veterans and other students. It suggested that future bond measures conform narrowly to Proposition 39 language and focus on construction of educational facilities:

Finding 1

The language of Measure Q was misleading. While Proposition 39 generally authorizes funding of buildings and land purchases even the name of the measure, “The Solano Community College District Student/Veterans’ Affordable Education Job Training, Classroom Repair Measure,” suggests otherwise.

Recommendation 1

Language used in future school bond proposals be limited to that which is stated in the authorizing statute.

References to veterans is an example of how campaign consultants have developed ballot titles, questions, and summaries that manipulate the emotions of uninformed voters who are looking at a ballot and deciding how to vote. Another example is the claim that “all funds stay local” or “all funds benefit neighborhood schools.” This statement ignores how taxpayers will pay the financial services industry for issuance fees and may end up providing more funds for interest payments to wealthy bond investors than for principal spent on design and construction of neighborhood schools.

These clever campaign tactics would probably withstand legal challenges based on California Elections Code Section 9509, which establishes a standard for a legitimate challenge to a title, question, or statement of a school or college district ballot measure. A complaint must have “clear and convincing proof that the material in question is false, misleading, or inconsistent” with state law.

Grassroots Activism on Bond Measures Is Difficult

1. Municipal Finance Is Confusing, Even for People Motivated to Understand It

As stated in a 2013-14 Orange County Civil Grand Jury report on Capital Appreciation Bonds, “This topic required extensive research. Numerous newspaper articles were reviewed…An extensive Internet search was conducted to learn about the mechanics of bond financing and the related mathematics.” An ordinary person may have difficulty understanding concepts and jargon of municipal finance. It’s also a challenge for anyone without education or experience in accounting to identify and extract relevant information from financial audits and official statements.

In particular, Capital Appreciation Bonds are difficult to comprehend. To complicate matters, accreted interest for this type of debt instrument is portrayed differently depending on whether accounting is done on a “cash basis” or on an “accrual basis.” In the generally accepted accounting principles developed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, each year’s interest payment is included as an expenditure for the year. This is accounting done on a cash basis. But in the generally accepted accounting standards for state and local governments developed by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, accreted interest on Capital Appreciation Bonds is not recorded as a current expenditure until the bond matures. This is accounting done on an accrual basis.

Translating these concepts into something easy to understand is critical for the public to evaluate the wisdom of proposed bond issues.

2. Centralized Data Isn’t Available to Compare Debt Finance Conditions of School and College Districts

Where does the public go to find out how a school or college district funds facility construction and how it compares to other educational districts in the county or state?

In most cases, state law has not assigned any state or local agency with the responsibility to collect such information and provide it to the public in an accessible format. Even for information that state law requires to be collected and published — such as waivers from tax and debt limits — agencies are not providing the information in a way that alerts the public to existing or potential problems.

The California State Treasurer’s office has a “California Debt Issuance Database” administered by the California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission that allows the public to search for certain information about individual bond issues. School boards are required to submit certain information and reports regarding the sale or planned sale of bonds to the California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission. This database is better than nothing, but realistically it is not a useful tool for the ordinary citizen.

3. Basic Financial Information Is Inaccessible, Especially at Smaller School Districts

Many school districts are not posting their state-mandated financial reports on their websites for public access. Useful documents that the public should be able to readily access include PDF versions of annual financial audits and bond program audits.

For cases in which financial reports are not available on the web, adequate response to public records requests is often elusive. E-mailed requests to educational districts to get these reports do not always result in a prompt response. In particular, officials in small rural school districts do not seem responsive to an outside individual or organization requesting the district’s financial information. Researchers for this project struggled to obtain financial audits that would reveal details of Capital Appreciation Bond sales with ratios of debt service to principal that are much worse than the Poway Unified School District.

4. “Private Placements” Sometimes Eliminate Official Statements as a Source of Data