Texas Supreme Court Sanctions Fraud

SCOTX Ultra Vires Constitutional Issue

By Mitchell Vexler, November 5, 2025

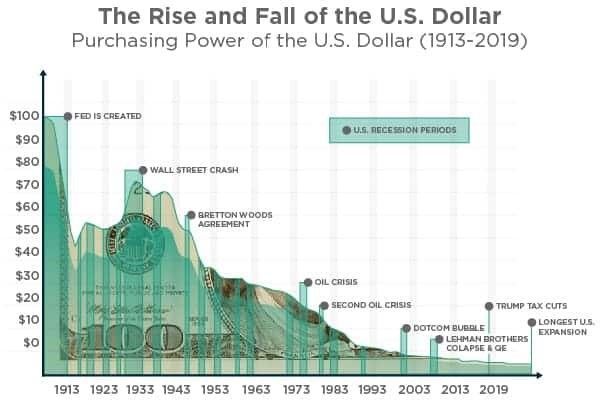

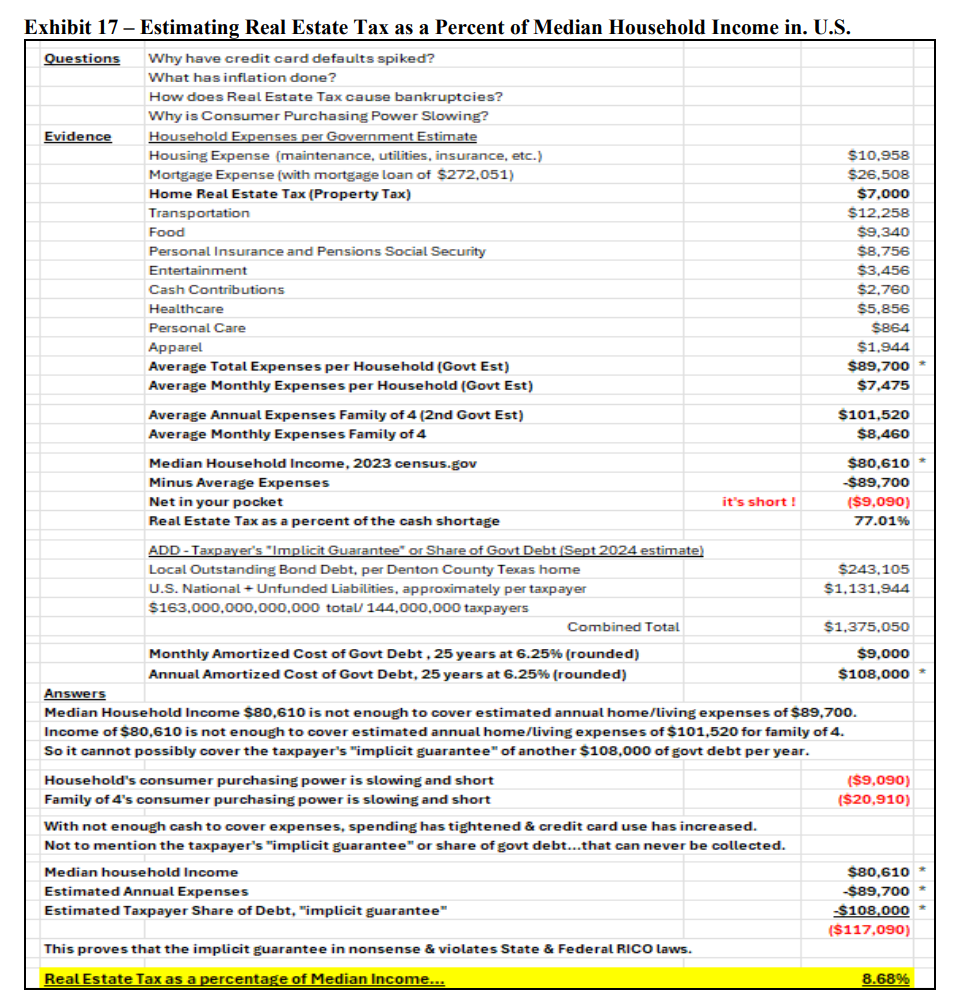

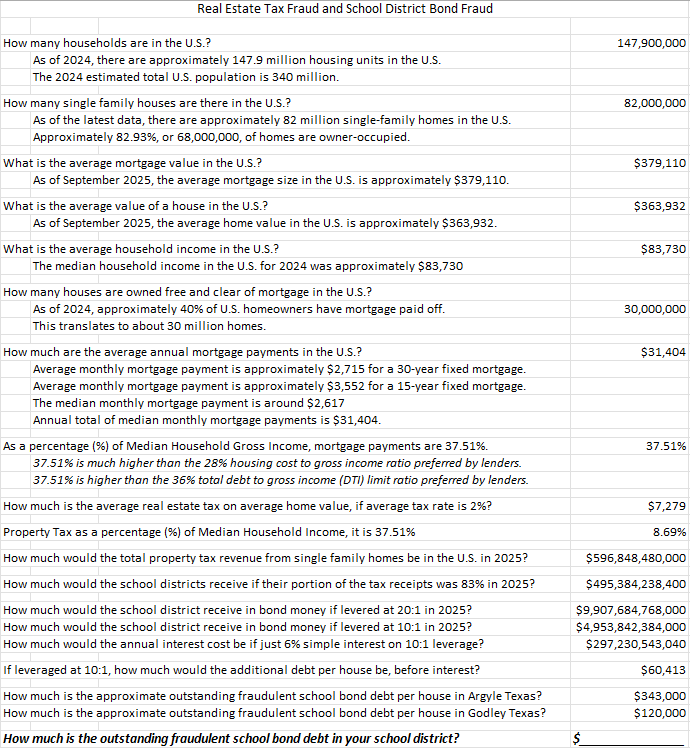

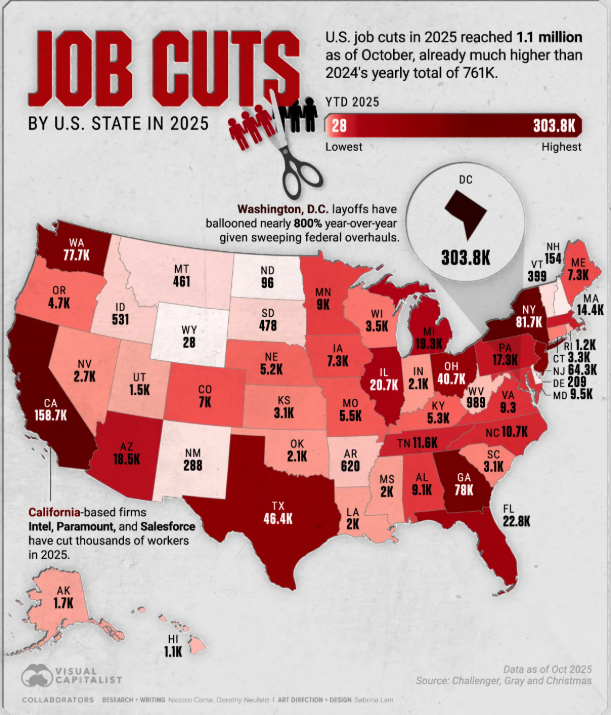

Not only is the equity in your home being stripped from you while you sleep, so are your constitutional rights! This should concern every property owner and every single citizen, because you are paying for it regardless of what State you live in. As goes California and New York, so goes Texas! As goes Texas, so goes the United States of America!

The Disappearing Doctrine: How Texas Rewrote Ultra Vires and Shielded Constitutional Overreach from Judicial Review.

How do we know?

We caught them and documented every step in the process of how the property owners have been defrauded financially and simultaneously suffered the hidden repeal of their constitutional rights.

Background: No. 25-0615 Case to the Supreme Court of Texas (SCOTX)

The concept of ultra vires in Texas was established through legal precedents, particularly highlighted in the Texas Supreme Court case City of El Paso v. Heinrich in 2009, which allowed lawsuits against government officials for actions taken beyond their legal authority. This doctrine serves as a narrow exception to the broader principle of sovereign immunity, enabling claims against officials acting outside their granted powers.

Definition of Ultra Vires

Ultra vires is a Latin term meaning "beyond the powers." It refers to actions taken by a corporation or government entity that exceed the legal authority granted to them. The opposite term, intra vires, describes actions within the scope of authority.

Contexts of Ultra Vires

Corporate Law

- In corporate law, ultra vires acts occur when a company engages in activities outside its charter or bylaws. Such actions are typically considered void or voidable.

- Most jurisdictions have limited the application of ultra vires in corporate contexts, allowing companies broader powers to conduct lawful business.

Administrative Law

- In administrative law, ultra vires claims can arise when government agencies exceed their statutory authority. Courts can review these actions to ensure compliance with legal limits.

- The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) allows for judicial review of agency actions that are deemed ultra vires.

Constitutional Implications

- Ultra vires can indeed be a constitutional issue, particularly when actions by government bodies or officials exceed the powers granted by the constitution or statutes.

- Courts may invalidate laws or actions that are found to be ultra vires, reinforcing the principle of limited government authority.

In summary, while ultra vires primarily relates to the scope of authority in corporate and administrative law, it also has significant constitutional implications when government actions exceed their legal limits.

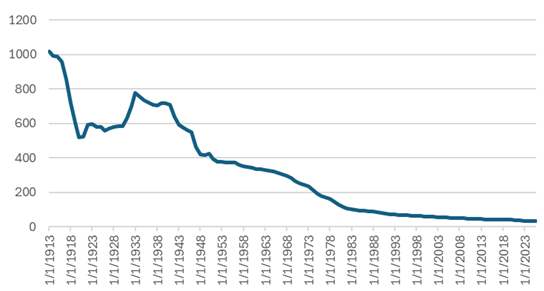

SCOTX denied the case to be heard with no explanation. Could it be that an intern did not understand the case and blocked it from moving forward…TBD. However, let’s examine the impact of this case not moving forward. The ramifications of SCOTX currently denying the case from being heard meaning that Ultra Vires can’t be determined in law, then A.) for what purpose does Ultra Vires exist? and B.) there is no law to protect the Citizens which invalidates the Texas Constitution under Uniform and Equal. If there is no law, then perhaps the approach by all property taxpayers should be… let’s all take a tax holiday for the 12 months and bring the school districts to bankruptcy, involuntary bankruptcy, and or conservatorship because the truth is that the vast majority of the school districts that raise bonds are insolvent and have been using the contorted hiding ultra vires as a method to cover up the necessity of the continued bond raises to pay for the compound cumulative interest on the outstanding bonds that are rolled out and interest rolled up instead of retiring the bonds.

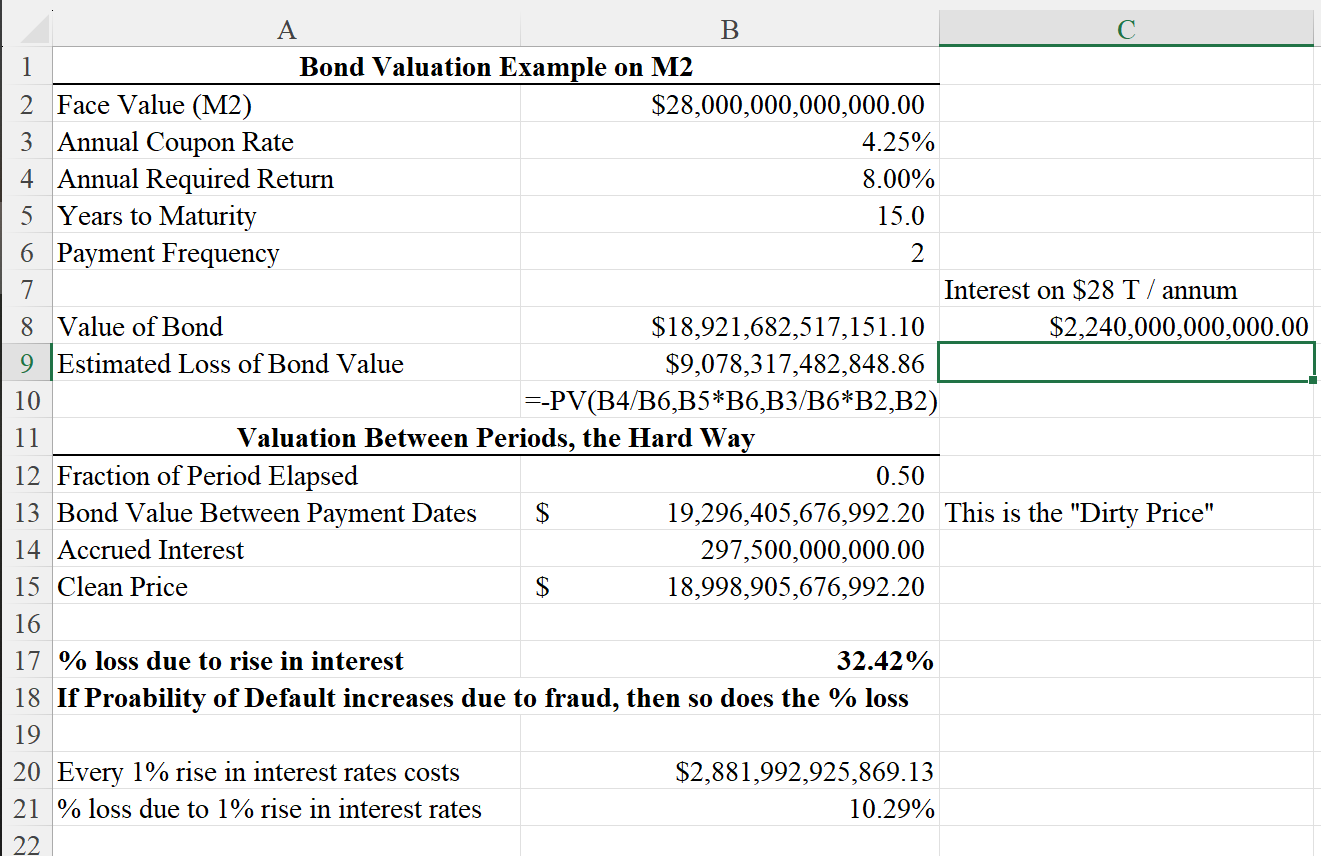

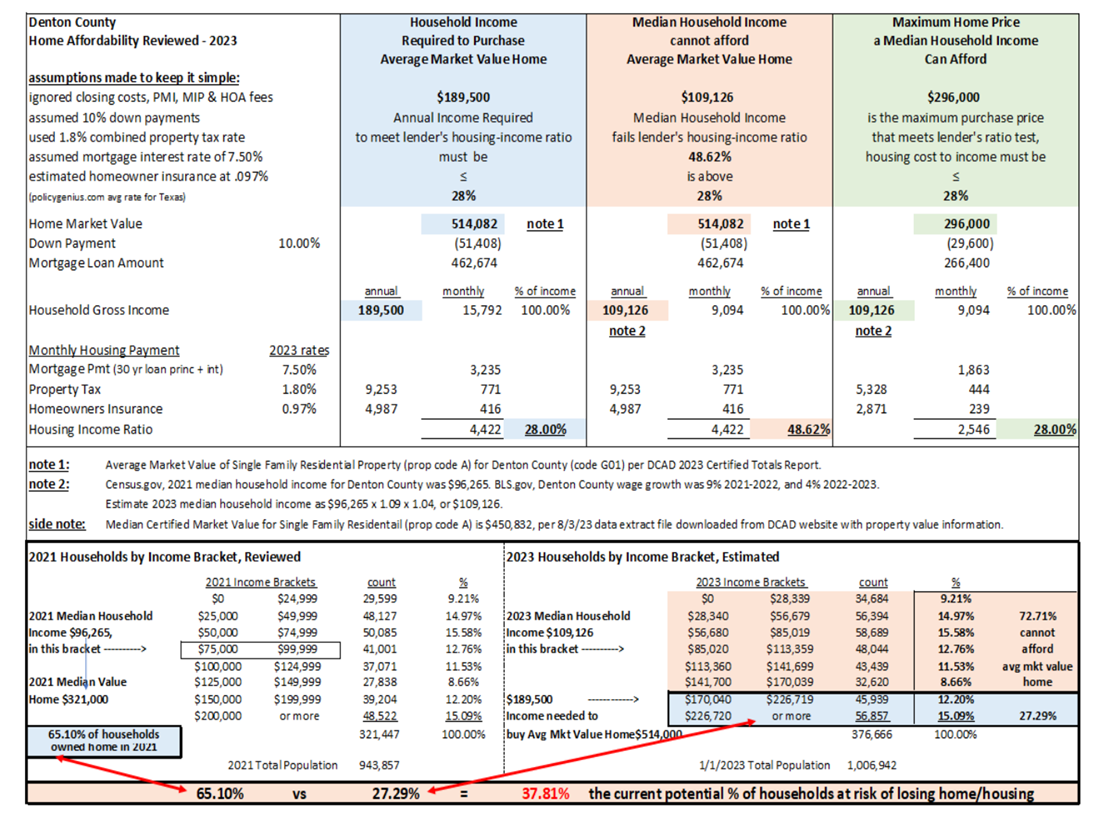

There is a very serious problem here in that nobody with a brain cell would agree to accept no protections under the law and have to accept the pre-determined budgets from a school district that has never seen a report on how much tax a property owner can afford, a school district that creates a wish list of money with no bids, no construction drawings, boosted operations and maintenance (O&M) numbers, fraudulent interest and sinking fund (I&S) with no publicly available evidence of how much in bonds is outstanding and how much in compound cumulative interest is outstanding, all of which is handed over the Chief Appraiser of the Central Appraisal District who has zero capacity to determine what fraud was committed by the School Superintendent and the School District Boards, and then the Chief Appraisers accept that fraudulent pre-determined budget, after being told to hit the pre-determined budget number, and then further expands, creates and “manipulates” fraudulent property values outside the confines of USPAP, Texas Property Tax Code, Texas Education Act, the Texas Constitution (Uniform and Equal) and The U.S. Constitution, not to mention a host of other State and Federal laws including RICO that are also being violated. This is the definition of a criminal conspiracy to defraud and the Attorney General, State Comptroller, State Auditor, and the courts have sanctioned it and right in the face of the very laws that are black letter of the law as each one of these entities has the obligation under law to prohibit the exact issues they have created.

What does it take to get the attention of SCOTX?

No action via denial to be heard by the SCOTX is sanctioning: no law, no application of the law, no uniformity of law, no maximum financial report or ability to determine how much any taxpayer can pay (thus tax lien foreclosures), fraud created by the School Districts because they simply state how much they want without bids or financial controls, or a maximum cap on households and property owners, and apparently never had a cap so the system has morphed into Systemic Institutionalized Moral Hazard and that is exactly what the SCOTX is supposed to prohibit, via the Ultra Vires and the Open Courts Doctrine that the SCOTX wrote in the Patel case.

Property Taxes, if they are to exist, must be fair and uniform. On its face, via the outline above, they are not and, again as stated above, that is because of the blank check allowed to fester and morph into Systemic Institutionalized Moral Hazard.

When you go to a grocery store, what you buy has weights and measures. You know what you are getting. Where are the weights and measures at the School Districts (i.e., maximum household affordability study) and where are the weights and measures at the CADs (i.e. the prohibition against fraud via over valuation and over taxation)?

HOW CAN SCOTX NOT REALIZE THAT ULTRA VIRES IS A CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE?

The following integrates the constitutional theory of ultra vires, the Heinrich precedent, and the factual nexus from the Texas State Auditor’s 2024 PSF Bond Report (No. 24-011).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Texas Supreme Court’s limitation of the ultra vires doctrine to a procedural exception to sovereign immunity—rather than a constitutional limitation grounded in Article II, § 1 of the Texas Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—violates the Due Process and Supremacy Clauses by insulating unconstitutional state administrative acts from judicial review.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

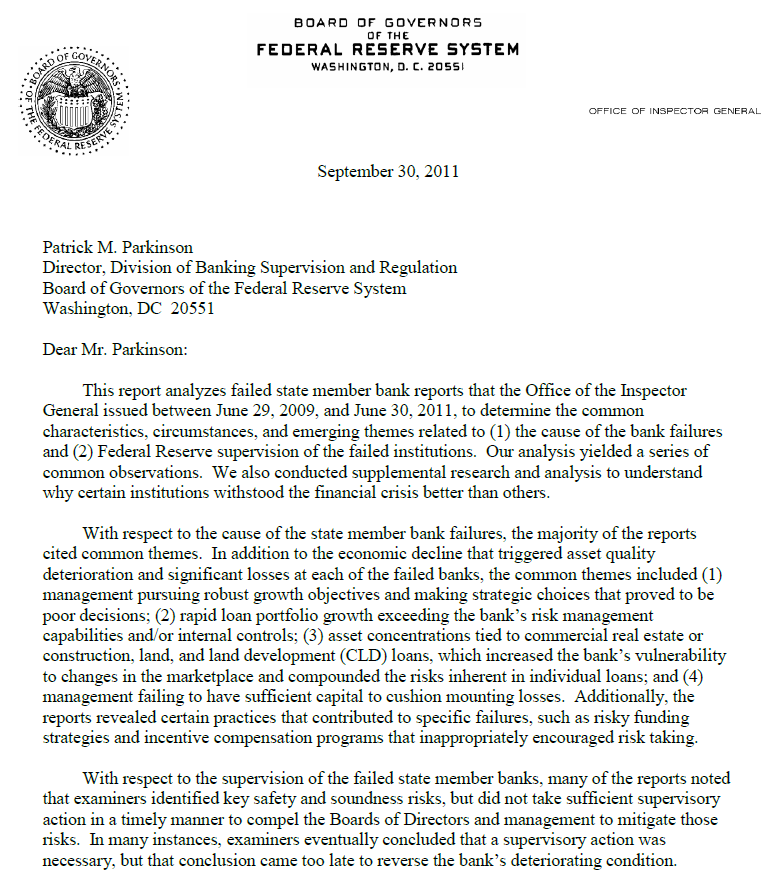

The Texas Supreme Court’s jurisprudence following City of El Paso v. Heinrich, 284 S.W.3d 366 (Tex. 2009), has redefined ultra vires from a constitutional safeguard into a narrow procedural device. In Heinrich, the Court recognized that sovereign immunity “does not protect state officials who act without legal authority.” Yet subsequent decisions have stripped that principle of its constitutional substance, allowing agencies to alter statutory mandates by rule without legislative or judicial constraint.

This case presents a clear illustration of that constitutional drift. In January 2024, the Texas State Auditor’s Office issued Report No. 24-011, certifying the State Board of Education’s 2023 revision of the Permanent School Fund (PSF) Bond Guarantee Program.

The Board unilaterally reduced its statutory reserve requirement from five percent to 0.25 percent, thereby expanding the State’s bond guarantee capacity by approximately $37.6 billion.

That change, adopted by administrative rule under 19 Tex. Admin. Code § 33.6, effectively rewrote limits fixed by

Texas Education Code §§ 45.053–45.0531, and redefined the “State Capacity Limit” outside legislative authority.

The State Auditor’s certification confirms that the Board’s act directly altered the constitutional and fiscal parameters of the PSF—an endowment created under Article VII, § 5 of the Texas Constitution for the “permanent support of the public free schools.” No statute authorized the 0.25 percent revision, and no legislative approval occurred. Nonetheless, Texas courts have declined to review such actions on sovereign-immunity grounds, deeming ultra vires arguments “non-constitutional.”

That refusal to adjudicate an overreach of delegated power denies Petitioners a forum to vindicate the constitutional principle of limited government and undermines federal supremacy over due-process rights.

ARGUMENT

I. The Texas Supreme Court’s Narrow Construction of Ultra Vires Conflicts with Federal Due Process Principles.

Under both Texas and federal constitutional law, the doctrine of ultra vires exists to prevent government actors from assuming powers not lawfully delegated. When state courts immunize such acts from judicial scrutiny, they extinguish the procedural mechanism by which citizens enforce the rule of law—a deprivation of property and liberty without due process. See Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803); Heinrich, 284 S.W.3d at 372-73.

By confining ultra vires to a mere “exception” to sovereign immunity, the Texas Supreme Court eliminates its constitutional function as a check on executive overreach. The result is a self-immunizing administrative regime contrary to the separation of powers mandated by Article II, § 1 of the Texas Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process.

II. The Permanent School Fund’s 2023 Rule Change Demonstrates Constitutional Injury Under the Supremacy Clause.

The 2024 State Auditor’s Report (No. 24-011) verifies that the Board’s reduction of its reserve requirement materially expanded bond guarantee capacity and altered statutory limits defined in the Texas Education Code.

Because the PSF’s guarantee capacity is also subject to a federal IRS limit—500 percent of total fund assets under IRS Notice 2023-39—the Board’s unilateral action implicated federal tax-law compliance and interstate bond markets. Administrative alteration of these parameters without legislative or federal authorization is an ultra vires act with direct constitutional consequences. When a state court declines review of such overreach on immunity grounds, it conflicts with this Court’s holdings that state sovereign immunity cannot be invoked to preclude federal constitutional claims. See, e.g., Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908).

III. Federal Review Is Required to Reaffirm the Constitutional Nature of Ultra Vires.

This Court should grant certiorari to resolve whether a state may, consistent with the U.S. Constitution, construe its ultra vires doctrine so narrowly that administrative agencies may alter statutory and fiscal constraints without judicial remedy. The issue implicates fundamental questions of state accountability, separation of powers, and due-process enforcement.

Texas’s reinterpretation of Heinrich now shields acts that are plainly beyond delegated authority—acts that, if committed by any federal agency, would be reviewable under the Administrative Procedure Act as arbitrary, capricious, or exceeding statutory jurisdiction. There is no lesser standard for constitutional accountability at the state level.

CONCLUSION

The Petition presents a recurring and nationally significant question: whether state sovereign immunity may bar judicial review of unconstitutional ultra vires acts. The SCOTX intervention is necessary to restore the constitutional balance and ensure that the principle “no one is above the law” remains enforceable in every jurisdiction.

School boards, while political subdivisions, are not state agencies within the meaning of Heinrich’s sovereign-immunity framework. Their powers derive from local authority under Tex. Const. art. VII, § 3, not directly from the state executive. That means traditional ultra vires claims (which assume an executive officer exceeding statutory limits) do not apply to school district bond authorities in the same way they would to a state agency like the SBOE, TEA, or the PSF Corporation.

However, it is crucial to understand and recognize that the State Board of Education’s 2023 rulemaking that enlarged the bonding capacity and altered the reserve requirement directly changed the financial reach of local school districts, effectively delegating an unlawful fiscal power to them.

So while the local boards themselves may fall outside the ultra vires reach, the constitutional injury arises upstream from the state entity (SBOE/PSF Corporation) that expanded local bonding authority in a way inconsistent with Tex. Const. art. VII §§ 2 & 5 (Permanent School Fund restrictions and state fiduciary duty).

REVISED QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Texas Supreme Court’s recharacterization of ultra vires as a non-constitutional procedural doctrine violates the Due Process and Supremacy Clauses when it immunizes state-level administrative acts that enlarge the fiscal authority of subordinate entities—here, local school boards—beyond constitutional and statutory limits established under Article VII of the Texas Constitution.

REVISED STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners challenge the Texas Supreme Court’s narrow construction of ultra vires, which has effectively removed constitutional accountability from state administrative rulemaking.

Under City of El Paso v. Heinrich, 284 S.W.3d 366 (Tex. 2009), sovereign immunity does not protect state officials who act “without legal authority.” Yet Texas courts now treat the doctrine as a limited procedural vehicle, refusing to apply it when state-level administrative actions empower or immunize local entities—such as school boards—even when the underlying rule violates constitutional limits.

The State Auditor’s Report No. 24-011 (Jan. 2024) documents that the State Board of Education reduced the Permanent School Fund’s statutory reserve requirement from 5% to 0.25%, thereby increasing the PSF Bond Guarantee Program’s guarantee capacity by $37.6 billion. This administrative change under 19 Tex. Admin. Code § 33.6 directly expanded the borrowing capacity of local districts under Tex. Educ. Code §§ 45.053–45.0531, without legislative authorization.

Because local school boards are not state agencies, they fall outside Heinrich’s ultra vires exception. The result is that a constitutional violation committed by a state-level fiduciary body (SBOE/PSF Corporation) cannot be challenged either as an ultra vires act or as an administrative abuse, leaving affected taxpayers and property owners without any judicial remedy.

REVISED ARGUMENT

I. The SBOE’s 2023 Rule Change Constitutes a State-Level Constitutional Breach, Not a Local Discretionary Act.

The State Board of Education, through the PSF Corporation, occupies a fiduciary position under Tex. Const. art. VII, § 5, which limits the use and leveraging of the Permanent School Fund. The 2023 reserve reduction altered that fiduciary structure, increasing guarantee exposure and extending fiscal benefit to local districts in excess of statutory authorization. Such action is ultra vires in the constitutional sense—not because a local board exceeded its powers, but because the state extended powers it did not lawfully possess.

II. Texas’s Restrictive Construction of Ultra Vires Denies Federal Due Process.

By refusing to review unconstitutional state acts merely because their downstream beneficiaries (school boards) are not “agencies,” the Texas judiciary eliminates any meaningful forum for enforcing constitutional limits. This denial of judicial review conflicts with the federal guarantee of due process and the foundational rule of Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), which forbids sovereign immunity from shielding unconstitutional conduct.

III. Federal Review Is Required to Reconcile State Sovereign-Immunity Doctrine with Constitutional Separation of Powers.

SCOTX intervention is warranted to clarify that a state may not, by definitional narrowing, remove constitutional accountability from acts that alter statutory and fiscal constraints established by its own constitution and affecting federal fiscal compliance (e.g., IRS Notice 2023-39 limits).

CONCLUSION

The question is not whether local school boards are subject to ultra vires review—they are not—but whether the State of Texas may, through administrative rule, constitutionally expand their fiscal reach beyond legislative limits while insulating itself from judicial scrutiny. That question goes to the heart of constitutional governance and warrants the SCOTX immediate review.

For Additional Evidence: